It is important to add that the school apparently played little role in shaping either career expectations or career patterns of most people in the early nineteenth century. To be sure, elementary schooling was certainly a prerequisite for that higher education which distinguished the holders of high-status occupations. But the expansion of primary schooling did not open up access to higher education. And in the early decades of the nineteenth century, at least, the differentiation between access to elementary and to higher instruction was compatible with (if not an actual result of) elite thinking and official policy... [T]he impetus for school reform was a rather contradictory one. On the one hand, reformers felt the need to have the socialization of all the children of the people directed from on high. Nothing was to be left to chance. On the other hand, however, the reformed educational system had to include guarantees than education would not instill ambitions to aspire beyond the social milieu of the family of birth or the limits of gender. The ideal school system from this perspective would be both comprehensive (including a place for every child) and limiting (not allowing free movement among the various parts of it). The clientele for each institution would be preselected on the basis of the child's presumed destiny, in turn suggested by gender and class origin.

This was not the assumption of all reformers. As we have already seen, a vocal minority genuinely believed in meritocracy—that all were not equal, but everyone (or at least all boys) should be allowed to compete equally for positions of policial and social dominance. That schools might serve the function of selecting "natural" talent was a belief that formed a comparatively subversive undercurrent in the ideologies feeding school reform; occasionally it pushed to the surface in democratic proposals. Still, the school systems that evolved as a result of the reformist urge—and so far all studies of both design and consequence are in agreement on this point—tended to reproduce rather than challenge not only the class and gender system as a whole, but even the social status of individuals in that system. That is, school systems rested on the assumption that schooling was a means of preparing children for their destiny as given by their social position and gender. In some countries, this was openly incorporated into the overall structure of the school system; in others, it occurred more subtly. But it was true everywhere that schools neither primarily served, nor were they intended to serve, the function of individual mobility.

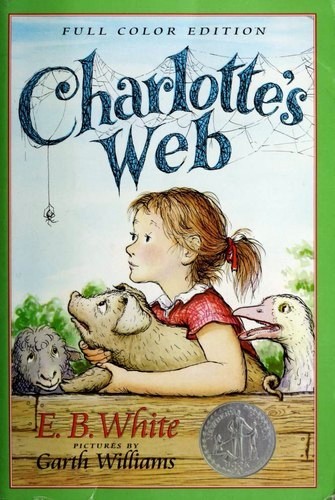

— Schooling in Western Europe by Mary Jo Maynes (Page 91 - 92)